The Grift: When Opportunism Wears Familiar Faces

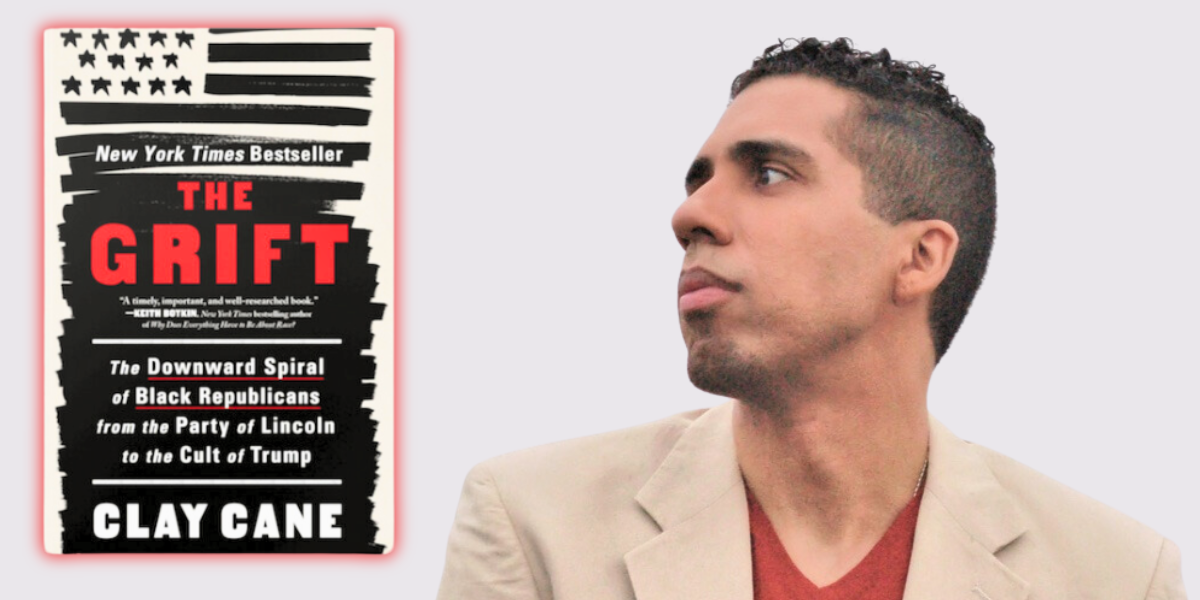

I explore Clay Cane's perspective in his evidenced-backed account of the downward spiral of Black Republicans from the party of Lincon to the cult of Trump.

I didn’t set out to read The Grift because I had a deep knowledge of Black Republicanism. To be honest, my introduction to Clay Cane’s work came at the crossroads of art and necessity. While building a character for the story I'm writing—one about a grifter's foray into conservative ideologies—I found myself searching for real-life models. That’s when The Grift: The Downward Spiral of Black Republicans from the Party of Lincoln to the Cult of Trump came up. It felt serendipitous.

Before I opened the book, I knew the basics about Black Conservatives: Frederick Douglass was a Black Republican and a name I held in reverence, particularly for his eloquent critiques of racism and slavery. What I wasn’t prepared for was how far Black Republicanism had traveled down a path from Douglass’ fight for equality to what Cane describes as opportunism, sometimes veiled in the language of progress and other times parroting white supremacist talking points verbatim.

History in Cycles

What stood out most? Cane doesn’t just list historical facts; he tells a story of transformation—of how Black Republicanism shifted from a collective fight for civil rights to a solo act of self-preservation. It's a theme that echoes loudly in today’s political landscape. Opportunism, it turns out, wears many faces, some of them startlingly familiar.

As someone who grew up seeing the likes of Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice sitting beside George W. Bush (especially during and post-9/11), I was conditioned to see these figures as symbols of progress (even if it was progress I disagreed with). After all, it was Black faces in high places, right? But Cane’s book challenged that shallow narrative. I now see how those roles, far from dismantling power structures, often served to reinforce them. These figures, while powerful in their own right, became tools for advancing white hegemonic interests—illustrating how Republicanism morphed from revolution to complicity.

Personal Reflections

The Grift didn’t just educate me—it made me uncomfortable in the best possible way. It forced me to reflect on the ways in which we, as a community, both uplift and betray one another. Cane’s portrayal of grifters—people willing to trade the collective welfare for proximity to power—made me think deeply about my own place in this historical struggle, albeit on the small level I occupy.

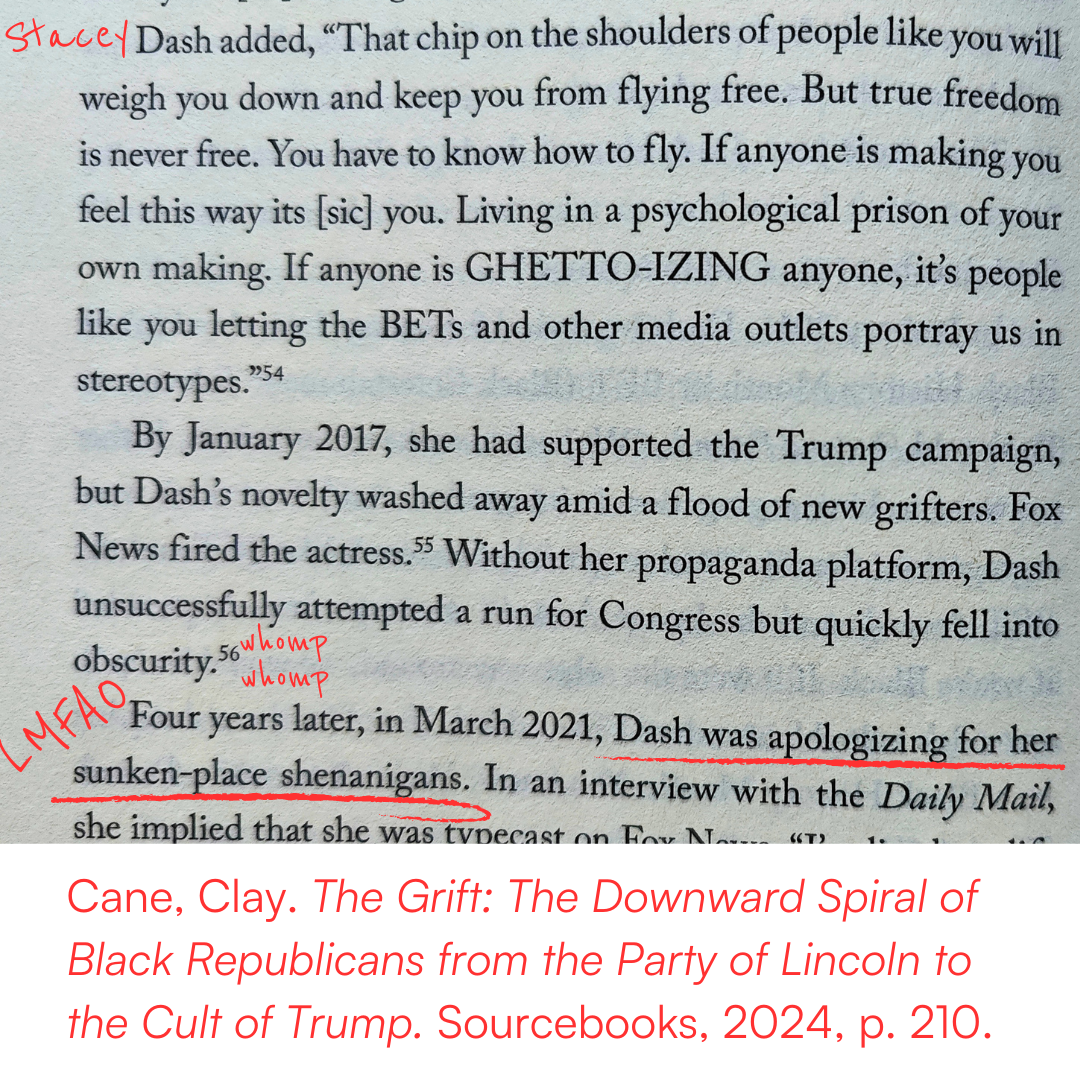

The Grift was also really funny sometimes! Having lived through the Stacey Dash grifting era, I could only appreciate Cane's shade:

I couldn’t help but feel a certain empathy (not to be confused with agreement) for those who engage in political grifting. Some of these individuals might truly believe they have no other choice but to “play the game” to survive. After all, being Black in this country has always meant having a target on your back and no idea where the gunman might be hiding. It's forced many to believe in self-preservation at any cost, leading to extreme individualism.

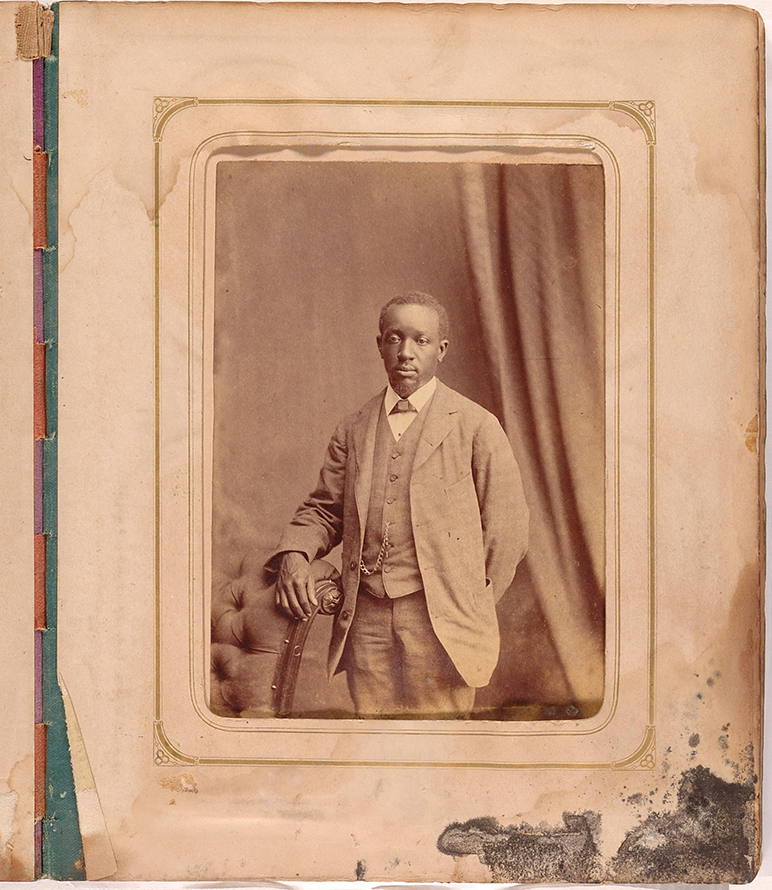

A prime example is in the case of Isaiah T. Montgomery, whom Cane features in The Grift's third chapter (72).

Wanting to learn more, I followed up on one of Cane's sources (see here) and was surprised to learn just how much of a quagmire Montgomery was in.

But Montgomery was also an astute political observer and he understood the realities of power in his time and place. Enfranchised by the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and technically allowed an equal opportunity to both vote and hold public office under the Mississippi Constitution of 1868, Black people outnumbered White ones in every decade from 1840 to 1940. Clearly, in this Black majority state of Mississippi, the first requirement of unchallenged White rule was Black disfranchisement. Having re-established White control by force and fraud in 1875, the “white line Democrats” — or “Redeemers” as they styled themselves — intended to dominate the political life of Mississippi by any means necessary. With an accommodating federal government increasingly willing to purchase North-South reconciliation by looking the other way, no prudent Black Mississippian could ignore that fact.

And Isaiah Montgomery, like his father before him, was nothing if not prudent. His father, Ben, chose his battles carefully. Eager to avoid racial conflicts that he could not hope to win, he had made it his life-long practice to cultivate friendships with influential whites. Ben set White people at ease by downplaying Black political aspirations, by affirming that voting was of “doubtful and remote utility” to the freedmen. Discussions of the “suffrage question,” he publicly asserted, are “more likely to produce contention and idleness than harmony.” These were calculated and soothing words, suggesting to White leaders, as one approving White newspaper editor put it, that Ben was a “sensible darky” and a “good citizen” who “attends to his own business [and] does not dabble in politics.”

Yet, examined in the context of his life and his times, his role at the convention seems neither treasonous nor puzzling nor inconsistent. By supporting a White supremacist initiative, he offered a way to end the “grave dangers” of racial conflict, “bridge” an ever-widening and deepening racial “chasm,” and “inaugurate an era of progress.” The Black right to vote in Mississippi, as he reasoned, had already been nullified by electoral fraud and by physical and economic coercion. By giving away rights they could no longer exercise anyway, Afro-Mississippians might gain the personal security and economic freedom necessary to advance themselves. (Emphasis mine.) Thus, given a “man’s chance,” having been allowed to prove their worth through right living, hard work, and practical education, the former enslaved and their descendants could expect someday to re-enter the body politic as equal citizens, free from the burden of racial prejudice.

While Cane acknowledges the racial realities at the time, he does not mince words nor does he attempt to misrepresent the horrors of the consequences. He calls out the treachery Montgomery pushed forth. He reminds us that Montgomery provided cover for white supremacists to continue sowing terror among the Black community in Mississippi. Cane quotes Frederick Douglass's response to Montgomery:

[...] The people with whom [Montgomery] makes this deal are restrained in dealing with the rights of colored men by no sense of modesty or moderation in their demands. They want all there is to be had and will take all that they can get. Sentiment is that no Negro shall or ought to have the right to vote (74).

And while Cane doesn’t absolve Black grifters of responsibility, he does a masterful job of highlighting the tension between self-preservation and community harm that some had to choose between. Thankfully, Cane doesn't let us cry for them for too long, reminding us that our boy Montgomery, already relatively privileged, personally prospered in the years following his choice to disenfranchise Black voters (74). It's a sobering reminder that for those with enough resources, these choices are strategic; for the community they claim to represent, they are devastating. (See Condoleezza Rice's section in "Chapter 7: Rice, Powell, and Bush" for a comparative point of view.)

A Timely Critique

There’s no doubt in my mind that Cane’s conclusions about Black Republicanism today are on point. The book demonstrates how these figures often become mascots for power rather than agents of true change. But where Cane shines most is in his exploration of this history as a cycle. It’s a reminder that today’s political grifters are not anomalies—they are the continuation of a long-standing tradition of political opportunism, one that has always sought to capitalize on proximity to power, regardless of its cost to the community.

I would have loved to see even more exploration of today’s most prominent figures—media personalities and politicians whose names fill our screens. But then again, history is still unfolding, so maybe Cane’s follow-up (hopefully there's a follow up, hint-hint!) will dive deeper into the present-day implications of this phenomenon.

A Call for Reflection

In a time when political opportunism is as pervasive as ever, The Grift is a necessary read for anyone looking to understand the deep-rooted complexities of Black political identity. On the one hand, we're happy to see one of our own advance, but on the other, only our due diligence can prevent us from giving power to someone who'll use it to cut the ladder behind them.

It reminds me of another warning to the larger community—the speech Dr. Ruha Benjamin gave at Spelman College in Atlanta:

University prepares us for life. And professor Ruha Benjamin didn't hold back when talking to graduating students in Atlanta, Georgia. She told them: 'Black faces in high places won't save us.' The message being, don't expect your rights to be defended by Black people holding professional, political or economic power. (@African_Stream)

Clay Cane's The Grift a warning: Not all skin folk are kinfolk. But it’s also a call to action, encouraging us to look beyond the rhetoric and examine the real impact of those who claim to represent us. Actions speak louder than words, after all, and Cane’s work underscores that truth in ways that demand our attention.